Factors Impacting Women’s Participation in Local Decision-Making Processes

This survey was conducted by the Development Policy Institute under the Building Positive Perception for Women Local Council Members Initiative funded by the USAID Jigerduu Jarandar (Active Communities) Project.

Summary

Under the USAID Jigerduu Jarandar (Active Communities) Project in June and July 2021, the Development Policy Institute (DPI) conducted an assessment to identify factors shaping Kyrgyz women’s participation in local decision-making processes. Findings and recommendations, presented in the full Survey Report, were used to inform the design of programs in support of women’s leadership and participation in Kyrgyzstan.

Methods

This mixed methods assessment employed focus group discussions, a survey and storytelling. Focus group discussions, conducted with 22 women, were used to inform the design of the survey questions and the response options. The survey was then administered online and in person to 142 participants. The questionnaire was formatted on Google forms and the link was disseminated via DPI’s WhatsApp groups comprising women local council members. Storytelling was then used to complement the survey data.

Findings

A total of 164 women from across the country participated in the assessment (142 respondents for the survey and 22 focus group participants). All participants were engaged in the Building Positive Perception for Women Local Council Members activity[1] and were active in civic engagement. Most were current, past, or soon to be local council members and ranged in age from 24-70 years old, with the majority between 40-56 years.

Barriers to women’s political participation: A lack of confidence and restrictive social norms were identified as key barriers. Yet, participants agreed that their own candidacies were possible because they had the confidence that, if elected, they were sufficiently competent for the role. Confidence alone however was said to be insufficient. Prospective candidates also needed to recognize that women should play a role in the public sphere—challenging dominant social norms that women are responsible only for domestic duties. In addition, confidence needed to be matched with capacity building for local council members that is particularly responsive to the specific needs of women leaders.

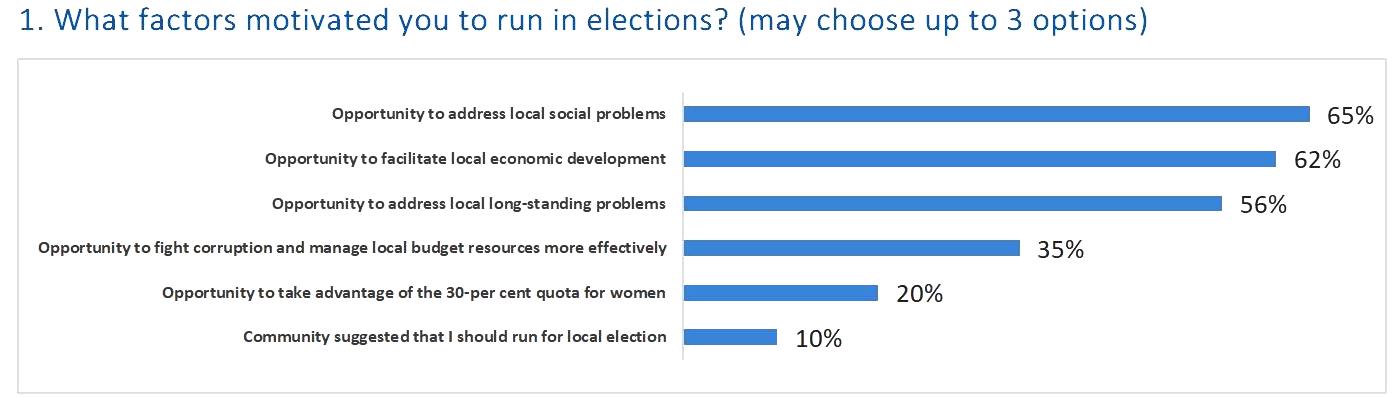

Motivation to run for office: The main motivation of women who decided to run for office was to solve local problems. Respondents in general attributed little importance to public recognition of any potential contribution. Nor were they as motivated as men, according to the results, by privileges and compensation accompanying public office. A common perception among respondents was that in comparison with men, once in office, women leaders tend to be more consistent, tolerant, fair, and transparent in their approach.

Leadership Ethics: According to most study participants, the integrity of local councils is undermined by unethical behavior, including the way in which women leaders are treated or viewed unequally by their male colleagues. There is a municipal code of ethics that applies to local councils, but it does not adequately account for gender equality issues.

Recommendations

Based on the findings, the following is recommended for future program design:

- Counter traditional norms that restrict women’s engagement in civic life.

- Increase women’s self-confidence through soft skill development.

- Support formation and strengthening of women’s coalitions and support groups to foster more civic engagement.

- Educate male representatives on ethical norms of conduct, including gender sensitivity.

- Develop a set of publicly funded measures to support women Local Council members.

Addendum: Survey Questions and Responses

The survey questions and responses are detailed below. The full Survey Report includes qualitative data from focus group discussions and storytelling exercises to supplement the analysis for each question.

Respondents selected motivation to address local social problems, address long-standing problems, and facilitate local economic development in their top three choices.

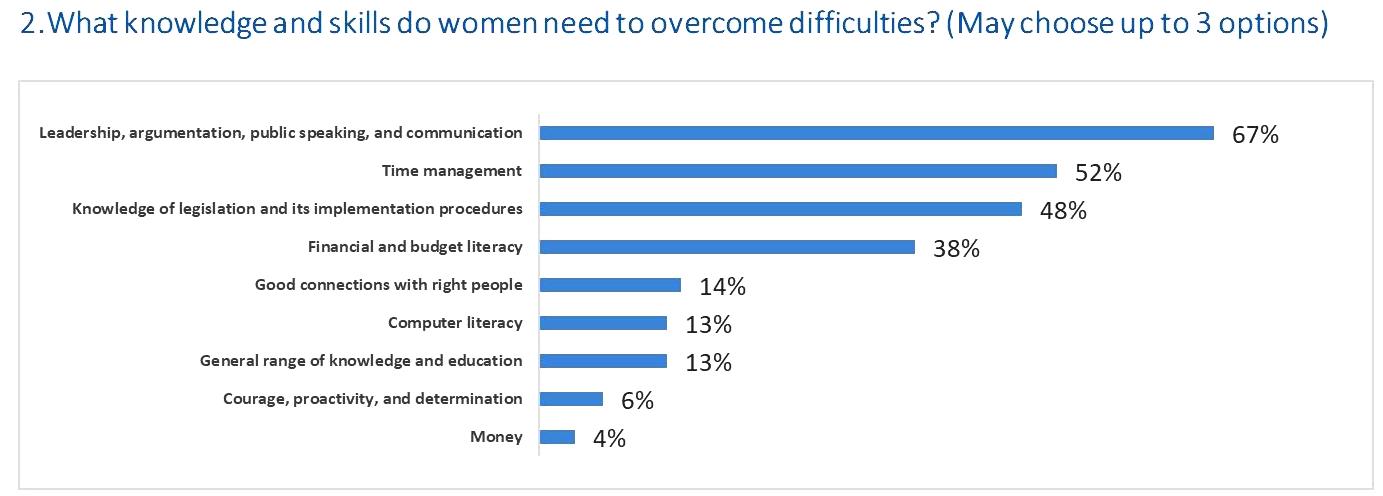

Respondents identified the top skills they perceive women needing: leadership, debate, public speaking, and the ability to communicate with different audiences.

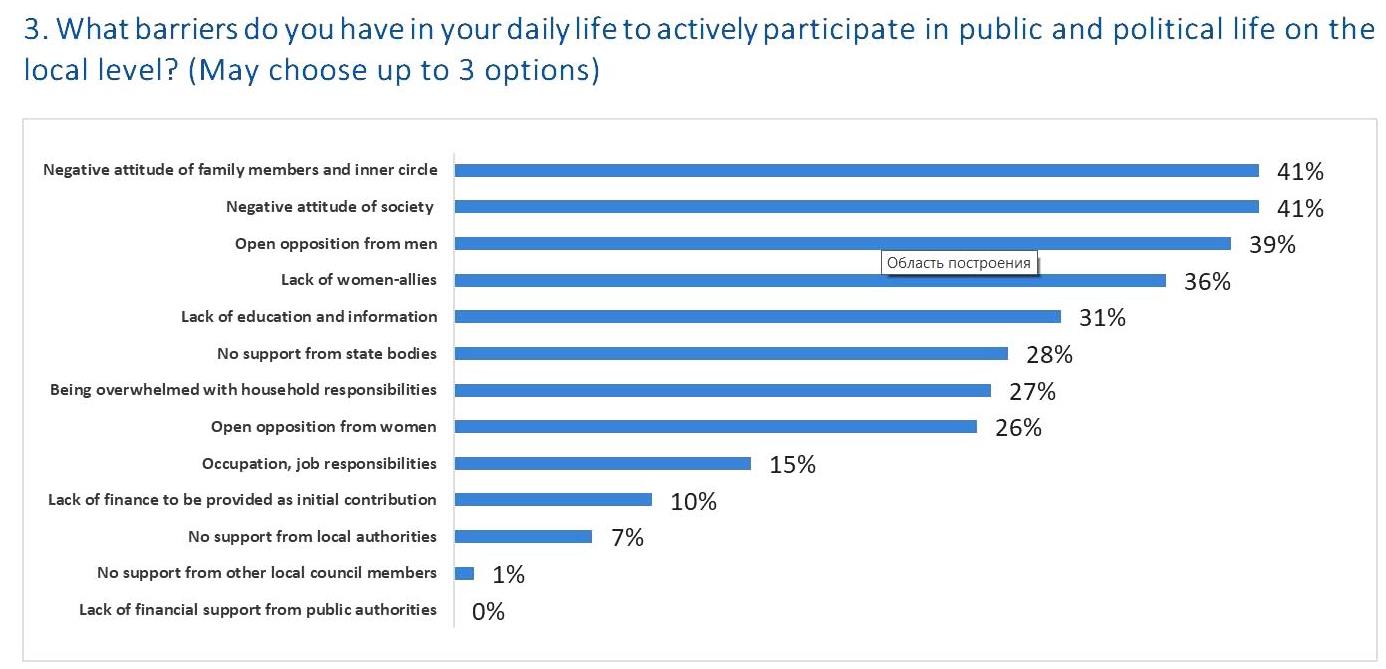

Respondents reported that lack of support from relatives of the immediate family and in-laws was one of the biggest barriers to active participation in public life. Two out of five women faced open opposition from men. More broadly, a proportion of respondents felt challenged by the negative opinions of community members about women’s political participation. Some respondents reported that they lacked alliances with other women with whom they could share their experiences and seek advice.

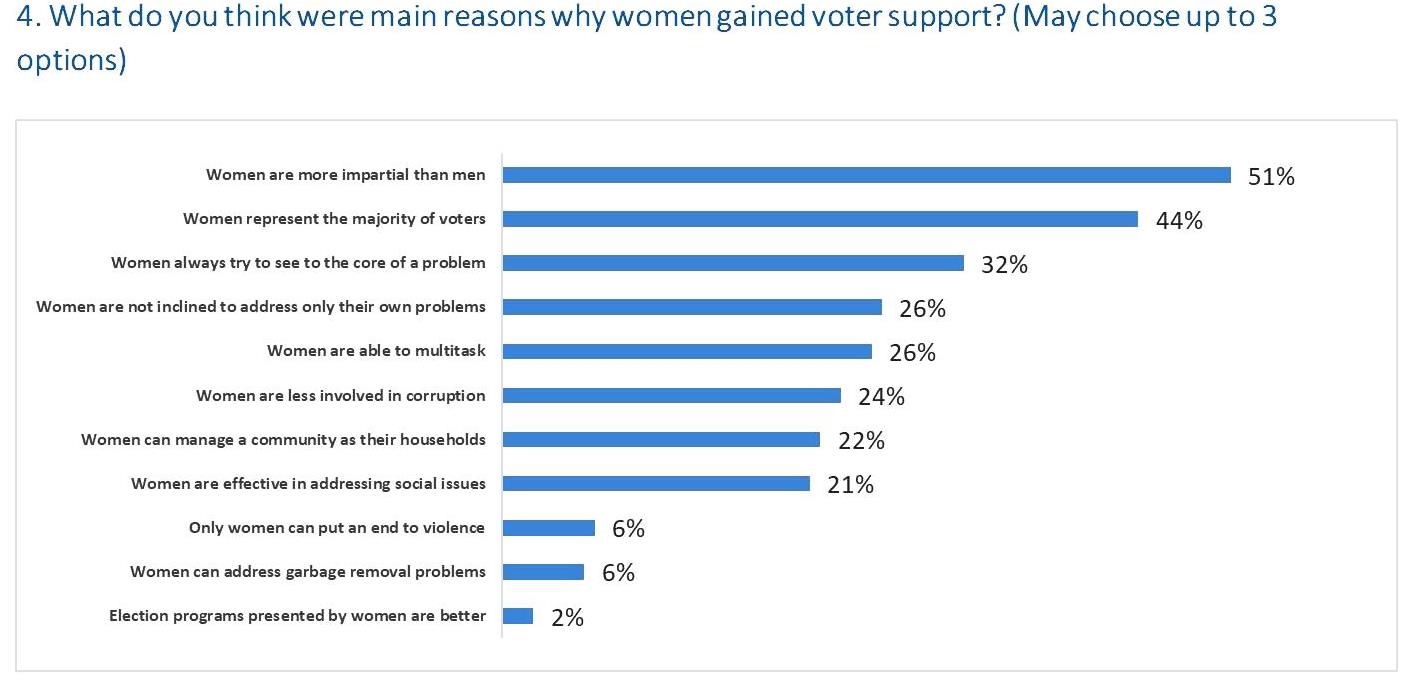

Impartiality was highlighted by respondents as a strength of women’s leadership in comparison with men. In the focus group discussions and in stories shared with researchers, women also reflected on their values and qualities of consistency, perseverance, and tolerance. Other qualities mentioned in the stories and discussions were honesty, attentiveness, and tolerance. Almost a third of the survey respondents identified as a strength the ability of women leaders to see the core of a problem. By contrast, women view men as more inclined to leave an issue unresolved and move quickly and inconsistently to other matters.

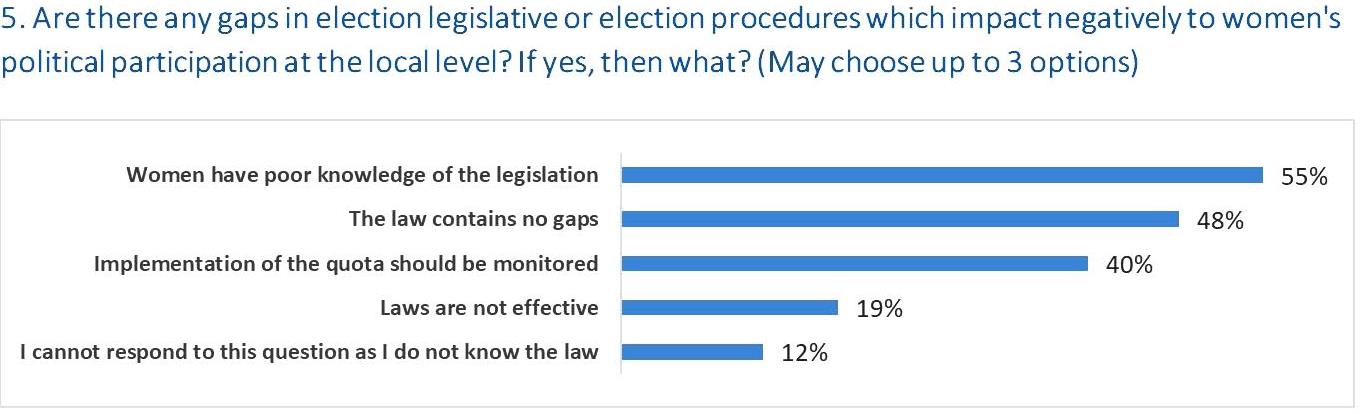

Almost half of survey respondents stated that there were no gaps in election laws, and more than half considered that women have a poor understanding of relevant electoral laws, while some reported that they do not know the laws well enough to comment on gaps. Importantly, more than one third of the respondents pointed to the need to monitor the implementation of quotas aimed at ensuring equitable participation by women.

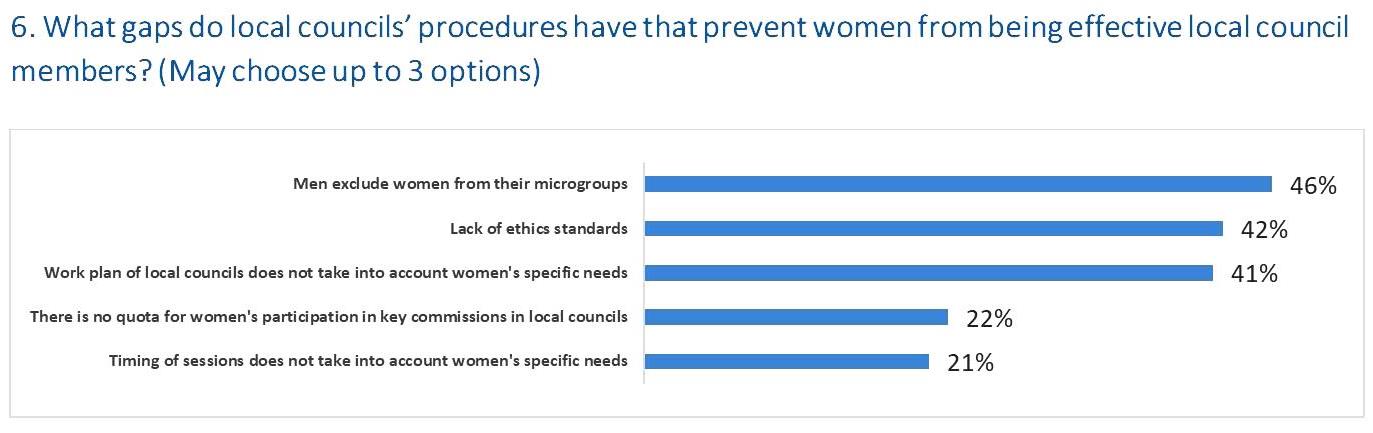

Men tend to create their own micro-groups, according to respondents, which have the effect of marginalizing and excluding women from Local Council deliberation. For example, 22% of respondents noted their marginalization from deliberation and decision-making about budgetary issues that are managed through commissions. Only a fifth of women identified quotas as the solution for council participation, suggesting the importance of other kinds of support.

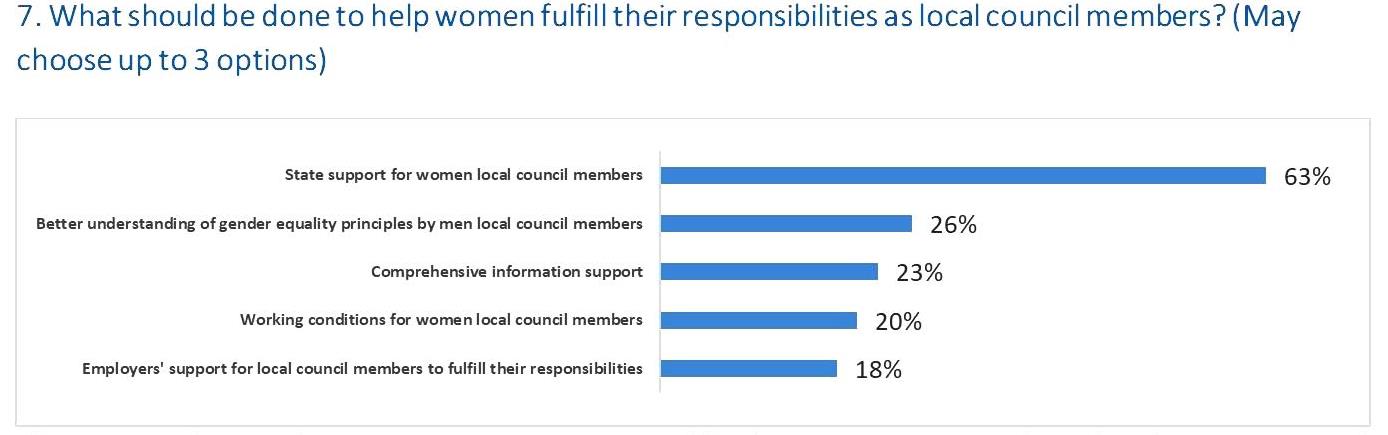

Almost two-thirds of respondents recommend public funding to support the role of women council members. A range of other measures have roughly the same relevance to respondents: gender-sensitivity training for men, provision of knowledge, improved working conditions for women, and more financial support for public activities.

[1] This activity is funded by multiple funders including the USAID Jigerduu Jarandar (Active Communities) Project.